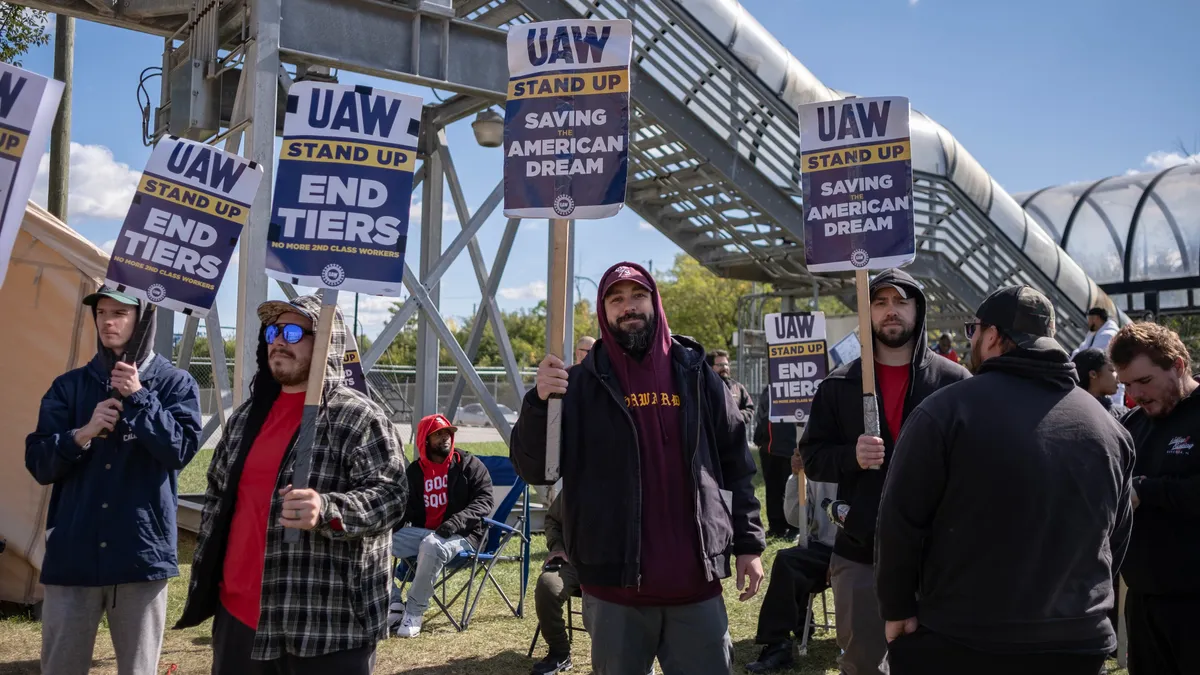

After about six weeks of strikes, the United Auto Workers won major concessions from the Detroit Three automakers. On Sunday night, UAW President Shawn Fain said the union would attempt to organize nonunion automakers in the U.S., such as Honda, Tesla and Toyota.

“One of our biggest goals coming out of this historic contract victory is to organize like we’ve never organized before,” Fain said during a Facebook livestream event Sunday. “When we return to the bargaining table in 2028, it won’t just be with the Big Three. It will be the Big Five or Big Six.”

Experts say the contracts could stimulate better wages and benefits and drive successful unionization efforts at foreign-owned auto plants. Nonunion companies may need to raise wages or improve working conditions to compete with their union counterparts.

The tentative agreements with General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, yet to be voted on by UAW members, include a 25% base wage increase over the life of the contract, reducing the time it takes to earn top wages from eight to three years, cost-of-living adjustments and the right to strike over plant closures.

A 2016 report from the Economic Policy Institute demonstrated that greater unionization in an industry is associated with higher wages for all workers, even if they’re not in a union. The report says unions set industry standards that nonunion companies need to meet to attract workers or to prevent union-organizing drives at their plants.

“If the [foreign-owned] plants stick to providing ‘near UAW’ compensation, wages will go up in foreign plants to keep pace,” said Stephen Silvia, a labor relations expert and professor at American University.

Yet corporate leaders warn they cannot afford UAW demands such as higher wages and pension increases because of the competition from foreign automakers.

“Toyota, Honda, Tesla and others are loving this strike because they know the longer it goes on, the better it is for them,” Ford Executive Chair Bill Ford said soon after the UAW struck the automaker’s truck plant in Louisville, Kentucky, in mid-October. “They will win, and all of us will lose,” he said.

UAW President Shawn Fain responded, saying in a statement that workers at foreign-owned plants “are not the enemy” but “the UAW members of the future,” signaling the union’s intent to expand to nonunion companies.

The UAW has already organized some EV battery suppliers, including Ultium Cells, GM’s joint venture with LG Energy Solutions in Lordstown, Ohio, and California-based startup Sparkz. Those unionization efforts are beginning to pay dividends for workers as the UAW negotiated a 25% wage increase with Ultium in August.

The UAW also won additional job security for Ford autoworkers as the manufacturer transitions from internal-combustion engine vehicles to EVs, a concession GM committed to first earlier this month. If UAW members ratify Ford’s tentative agreement with the union, the UAW will likely eventually represent employees at the automaker’s forthcoming $3.5 billion battery plant in Marshall, Michigan, and BlueOval City, also known as the Tennessee Electric Vehicle Center, under construction near Memphis, Tennessee. UAW-represented Ford workers will also have the right to transfer to the automaker’s future EV facilities in Kentucky and Tennessee.

In previous decades, UAW organizing at nonunion auto companies was mostly unsuccessful. Silva said coordinated anti-union pushback from employers and weak, top-down — rather than grassroots — organizing contributed to the union’s lack of success. And automakers continue to move south, including companies’ EV manufacturing plants.

“I don’t think it’s any mystery that automakers came to the South to try to take advantage of the various forms of labor exploitation that they can carry out here,” said Will Tucker, southern program director at worker advocacy group Jobs to Move America, which has worked with the UAW.

Silvia’s book “The UAW's Southern Gamble,” which details how the UAW failed to organize foreign-owned auto plants in the South, was published in May.

Silvia said many auto plants operate in rural parts of the South, where unionization is rarer, and workers, often living far apart from each other, are harder to organize. And specific state characteristics, such as right-to-work laws that allow workers to opt out of paying union dues or anti-union politicians who campaign against union efforts, also challenge organizers.

Volkswagen Group, for instance, had planned to recognize a Tennessee plant’s union voluntarily in 2014 — the automaker works closely with unions in Germany, where it’s headquartered — but balked following pressure from anti-union state politicians. The union drive ultimately failed in 2019.

Employers are usually the biggest challenge to unionization, experts say.

“Foreign automakers developed a sophisticated union-avoidance playbook” that included both “carrots” and “sticks,” Silvia said in an email. Carrots have included “near UAW” compensation and giving to local charities, he said, while sticks involved screening new hires for pro-union sentiments, intense anti-union messaging and indirect threats of job loss.

Could this time be different? Silvia thinks so. For one, he said, “The tactics of the union-avoidance playbook are now well known.”

To build effective campaigns, Silvia said, “Organizers need to develop and execute more holistic organizing drives that focus on building and maintaining grassroots support and draw more effectively on the resources of the community.”

Silvia pointed out that the UAW recently hired a new union organizing director with experience running grassroots campaigns rooted in communities.

“Irrespective of the automakers’ strategy [in] coming to the South, the fact is southern workers are inspired by the actions of the UAW,” Tucker said. “It’s only a matter of time before workers in the South demand what they’re owed.”

Earlier this year, more than 1,000 workers in Georgia unionized bus maker Blue Bird with the United Steelworkers. As for the UAW, while no major foreign-owned plants are union, several southern auto suppliers and other manufacturers are unionized with the UAW, including GM’s assembly plants in Spring Hill, Tennessee, and Arlington, Texas.

Some foreign-owned automakers have also expressed their views on possible future union drives. Volvo, for example, “respects workers’ rights to choose whether or not to unionize,” a company spokesperson told South Carolina’s Post and Courier. BMW, however, said it would “vigorously oppose” any attempt by workers to unionize.

In recent years, the UAW helped organize campaigns at a Nissan plant in Mississippi in 2017 and the Tennessee Volkswagen plant in 2019. Worker organizers at these plants, already experienced, may be motivated by the UAW’s wins to try for a union again.

Bill Sokol, a labor-side lawyer at California-based firm Weinberg, Roger & Rosenfeld, said Big Three auto executives should use negotiations to level the playing field between GM, Ford and Stellantis and nonunion automakers.

“The smartest thing that management could do to compete with [nonunion companies] is work out a really healthy contract for their workers because then the UAW can go [unionize] those plants down south,” Sokol said, noting that a strong contract could motivate nonunion workers to join the UAW.

If more automakers were unionized with the UAW, he said, that could result in pay and benefits parity between the Big Three and other auto companies.

“By fighting against the union,” Sokol said, the Big Three were “actually undermining their own competitiveness with all those nonunion plants.”